Four farmers eventually provided the necessary land for the factory site. In the Limerick Leader of October 7th 1972, Martin Ryan wrote an article headed "Limerick Farm costs £1000 an acre·. It read “a staggering £990 per acre Irish has been paid for agricultural land in Co. Limerick". This was in the Kilfinnan area, but it concurs with a neighbouring resident's observation of the rise in the price of land.' When Ferenka came around, it was the first hike in land prices locally".

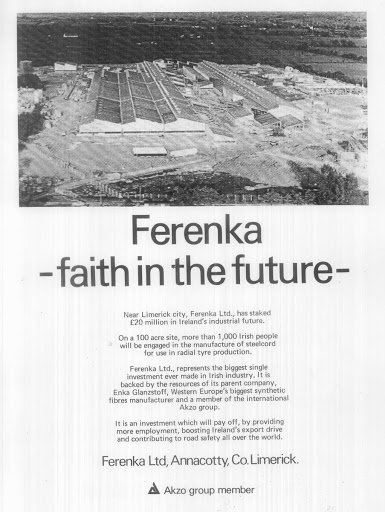

Ferenka, itself was a subsidiary of Enka, one of the groups of companies which made up the AKZO Group. Construction of the twenty million-pound Dutch plant was underway by May 1971. When Ferenka got off the ground in March 1972, they were manufacturing steel-cord for tyres. At this stage, Ferenka was employing two hundred and twenty -three people. On the Limerick Leader of September 2nd, 1972, an article by Tony Purcell read "Wanted, 500 men to work at Ferenka Factory". In it he states "a further indication of the tremendous boon the gigantic Ferenka Factory at Annacotty, Co. Limerick, is to the Mid-Western region is that a major recruitment drive for an extra 500 men is underway to meet production targets”.

By this stage, five hundred people were employed in the factory, and by the end of the year, it was hoped to have the labour force one thousand strong. The factory was described as a “carefully designed complex, built to harmonise with the pleasant rural landscape and to provide the best possible working conditions". As to these aims, it did succeed in the former. As one former employee succinctly put it, 'for such a large plant, it fitted very well into the surrounding countryside". The road leading to the plant, off the main Dublin-Limerick road, for generations known to inhabitants of the area as Ballyvarra Cross became known as Ferenka Cross overnight.

Advertisements

The Limerick Leader of September 9th and September 16th carried advertisements looking for future employees for the factory. The advertisement read; "Ferenka Limited. Limerick. Male machine operators. Vacancies for the above positions exist in our modem factory in Annacotty, Co. Limerick. Applicants should be in the age group of 18 to 45 years. The job entails four-cycle shift working. Previous experience is not necessary, as full training will be given. These positions offer excellent wages and conditions and a secure job". So went the advertisement but how did this work in theory?

The Limerick Leader of September 9th and September 16th carried advertisements looking for future employees for the factory. The advertisement read; "Ferenka Limited. Limerick. Male machine operators. Vacancies for the above positions exist in our modem factory in Annacotty, Co. Limerick. Applicants should be in the age group of 18 to 45 years. The job entails four-cycle shift working. Previous experience is not necessary, as full training will be given. These positions offer excellent wages and conditions and a secure job". So went the advertisement but how did this work in theory?

"Four cycle shift working was a very very hard shift", to quote one worker. The former Ferenka employee continued, 'It meant that you have one free weekend in four. The other three weekends you were either on days, evenings or nights, so 'twas very hard to plan anything for the weekend. That caused problems there, especially in the summertime".

Wages were a debatable point where a lot of the former employees were concerned. One person described them as "poor enough", while another remembered taking home "maybe thirty, thirty-five pounds a week which was not bad". Another described the wages as "fair".

As to the non-experience of people entering the plant, that was seen by many as a dangerous flaw. One interviewee said, "they hired university graduates with no ability to relate to the workers ”. This corresponds to another's assessment of the situation. He put it thus; "when the Germans were asked to jump, they would ask 'how high?' the Irish, on the other hand, would ask “Why?” Allied to this was the number of small farmers and rural people in general who were employed in Ferenka. This individual explained that "as soon as the weather was fine, they were off to cut the hay!" Of course, that was hardly surprising, as those people, some being small farmers were working in Ferenka to supplement their income.

With the wisdom of hindsight, a former employee who held a management position told me, "The overriding thing here was the horrendous shift system that was in Ferenka. It was doomed to failure. You couldn't get any harmony or association unless that was changed and I'm afraid from a personal point of view I don't think we did enough to look widely enough at the situation". The staff relations and human resources area should have been looked at far more widely, and more understanding is given to how a shift system should work in a steel cord factory. "People were tired and exhausted from the shift system."

These allegations were given credence in the report Industrial Relations in Limerick City and Environment by Joe Wallace, which was undertaken as part of the National Institute for Higher Education's (NIHE) " Employment Research Programme. It reads, "In 1974 a survey of 225 workers in the plant carried out by a junior member of the personnel department identified five main areas of discontent among the manual employees.

These were the four-cycle shift system, the rigid attitude of management, pay and conditions and the pre-production agreement and failures of union service. Top management, however, rejected these findings".

With all this simmering dissatisfaction among the workforce, it is no wonder that there was a high rate of absenteeism. The alleged causes of the strikes and lockouts ranged from a disagreement regarding interpretation of the agreement to wages to dismal working conditions and various suspensions.

However, it must be said that not all in top management were unsympathetic to the workers’ plight. This is seen in a letter from Fr. Donal O'Mahony, who was a negotiator at the time of the Herrema kidnapping. In it, he relates the following: "Teide Herrema contrary to what some had thought at the time had made a strong case against any closure. One of the industrial relation difficulties Ferenka had at the time was in the area of production.

As Herrema sympathetically said to me, many of the employees were working in a factory environment for the first time, some coming from a rural background. So bad timekeeping became one of the problems.

On arriving late for work, some workers would say they would stay on a bit later in the evening to make up as it were. That, of course, was in tune with the lifestyle and psychology of many rural people in Ireland at the time, but not for the modern management of the factory in Co. Limerick. Fr. O'Mahony went on to say that Dr Herrema had defended them before the board in Holland. The priest states an obvious fact. "Ireland in 1975 was very different to the Ireland of 2000, and that includes trade union - employer relationships also".

Dr Krienhoff was the Chairman of the parent company in Holland at the time of the Herrema kidnapping. He came to understand in a new light, what Teide Herrema had said to him many times before, about the potential of the Irish workforce.

Largest single investment ever made in Irish industry

The company represented the largest single investment ever made in Irish industry. Once again referring to Joe Wallace's report notes that the Industrial Development Authority approved grants amounting to £12,424,000. The progressive management outlook referred to in the Limerick Leader article of September 2nd, 1972, was referred to by a former employee who held a management position at the plant. In our interview, he explained to me, "the company introduced quality control management.• He went on to say that people are only talking of introducing it now, some twenty-five years later, which beggars the question was Limerick ready for such a massive overhaul at the time. I consulted Joe Wallace. Joe replied, "I think no matter where Ferenka went, it would have had problems". He was "very strongly opposed to the thesis that it was a Limerick problem. It was uniquely a Ferenka problem·. In its essence, quality control management meant that everyone was on the same team. According to the former manager, "it worked to some extent". He went on to say that it was an evolutionary period in terms of industrial practice and standards. The noise levels, protective equipment, quality standards and health and safety standards all did conform ·quite rigorously" to the standards of the day.

The company represented the largest single investment ever made in Irish industry. Once again referring to Joe Wallace's report notes that the Industrial Development Authority approved grants amounting to £12,424,000. The progressive management outlook referred to in the Limerick Leader article of September 2nd, 1972, was referred to by a former employee who held a management position at the plant. In our interview, he explained to me, "the company introduced quality control management.• He went on to say that people are only talking of introducing it now, some twenty-five years later, which beggars the question was Limerick ready for such a massive overhaul at the time. I consulted Joe Wallace. Joe replied, "I think no matter where Ferenka went, it would have had problems". He was "very strongly opposed to the thesis that it was a Limerick problem. It was uniquely a Ferenka problem·. In its essence, quality control management meant that everyone was on the same team. According to the former manager, "it worked to some extent". He went on to say that it was an evolutionary period in terms of industrial practice and standards. The noise levels, protective equipment, quality standards and health and safety standards all did conform ·quite rigorously" to the standards of the day.

The health and safety standards adhered to in the plant is another aspect of the Ferenka story. A front-page article in the Limerick Chronicle dated April 13th 1974, reads "Largest Medical Unit at Ferenka". It reads as follows; "the unit headed by Dr Stephen Flynn includes six fully qualified nurses ensuring a twenty-four-hour service for the fifteen hundred employees of Ferenka Ltd". The medical unit began in a "small way" when the factory opened in 1972, "but was then expanded into a full and comprehensive service to the company, with a full complement of trained staff to run it" stated the Chronicle.

When I interviewed Dr Flynn about his experiences there, he stated that he had responsibility for running the Occupational Health Department in conjunction with Nurse Maureen Anthony, and later Nurse Alice McGivern both of whom had occupational training and four staff nurses, Nurse Maureen Neville, Margaret Finucan,e, Mary Gallagher and Mary Quinn. There were two levels of service provided. One was an accident and emergency service where injuries and accidents related to the workplace could be treated.

These ranged from "slips, trips, minor cuts and puncture wounds associated with the steel cord itself - as there were sharp ends and a lot of manual handling of the actual product itself, at various stages of production. Other problems included burns and muscle problems from people ·pulling and dragging· etc. In general, the kind of things you would expect from a plant", according to Dr Flynn, there was not any particular pattern of injury there.

The other aspect of the occupational health department was occupational health surveillance, "where people had medical screening before they entered the plant to see what their general health was like and to make sure they were fit to do the job. They were also screened to ensure that the job wasn't going to have any adverse effect on their health". Also, there was screening at regular intervals, such as checking their hearing and checking their lung function. These screenings were done because the factory was very dusty and noisy.

In the Limerick Chronicle article, it had stated that the Medical Unit aimed to protect the employees' health and to improve the working environment by working in conjunction with the Company's Safety Officer. I asked Dr Flynn if they had succeeded in their aims. He answered, as far as was possible in the affirmative. He stated "it was a short period to know if we had achieved our aim of protecting the workers' health. We simply did not have time for a long enough survey, but there didn't appear to be any incidents of noise-induced hearing loss”. This tallies with another assessment of the company as being "very committed to the health of their employees”.

Dr Flynn spent some time with Dr Verlin, who was Chief Medical Officer with AKZO and who also lectured in Occupational Medicine at Nijmegen University. There was a very large research Department in Arnhem, and while there he "witnessed the input they put into trying to control the noise levels, control vibration, and factory dust levels. "Then we also looked at what would be the model for health surveillance, in other words, seeing what test we need to do with the various employees·. It was just a case of imposing an already established occupational programme in Annacotty. They were given adequate resources to do so". As far as one can ascertain, the medical facility was one of the successes of Ferenka.

Kidnapping

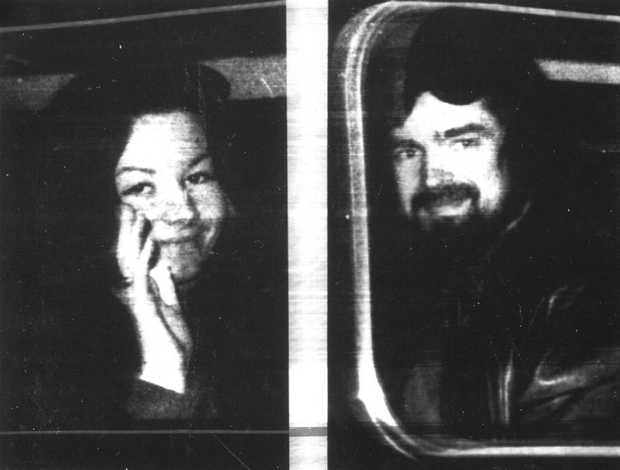

Another aspect of the Ferenka Story was the drama which unfolded beginning on October 3rd 1975. It involved the kidnapping of the Managing Director Dr Teide Herrema by Eddie Gallagher and Marian Coyle. On the day of the kidnapping, another unofficial strike was in progress at the troubled Ferenka plant. When word came through it was thought that "some of the workers had nabbed him". However, this soon proved not to be the case, and the picket was immediately called off. According to one source ", if anything outside of Tops of the Town united the workforce, I think the Herrema kidnapping was probably one of the main reasons that we tried to get things together."

Another aspect of the Ferenka Story was the drama which unfolded beginning on October 3rd 1975. It involved the kidnapping of the Managing Director Dr Teide Herrema by Eddie Gallagher and Marian Coyle. On the day of the kidnapping, another unofficial strike was in progress at the troubled Ferenka plant. When word came through it was thought that "some of the workers had nabbed him". However, this soon proved not to be the case, and the picket was immediately called off. According to one source ", if anything outside of Tops of the Town united the workforce, I think the Herrema kidnapping was probably one of the main reasons that we tried to get things together."

On the 4th October, a march was held in Limerick city organised by the unions and middle management to free Dr Herrema. "Shock" and "revulsion” were the two phrases which described people's opinion of the kidnapping, now almost a quarter of a century later. One interviewee spoke of the many worker's wives who were hospitalised with "nerves" during this time. Another interviewee who worked as a driver in Ferenka recalled his time there. Speaking of the morning of the kidnapping, he relayed the following story.

"Dr Herrema was only down the road a hundred yards from his own house; it was the one morning he had decided to drive himself.

He was caught at Mick Sutton’s gate. Usually, another driver (named) or I used to drive him. Word came through at 10 a.m. that he'd been kidnapped. They didn't know where he was; it was thought that the fitters union had done it as a prank". This concurs with a management view of the day in question, already alluded to that “it was thought that some of the workers had nabbed him". However, that was not the case. To quote a former employee. "it was real outsiders had done it”.

Recalling what happened locally, one resident remembers the soldiers “searching everywhere” They set up a roadblock close by the National School in Ahane providing the pupils with many hours of free amusement watching their parents and neighbours being questioned as to the whereabouts of Dr Herrema. There was an appeal made in a newspaper article of the time by Chief Superintendent Kenny to the effect that one should watch one's neighbour, as the search widened and there was no sign of the man to be found.

The reaction of this interviewee to the kidnapping was one of "surprise and disappointment". "Dr Herrema was a gentleman; he took part in every outing that was, in every social evening”.

This former employee believed the kidnapping took twelve months to plan. He took part along with the entire workforce from Ferenka in the march to free Dr Herrema.

They assembled at Pery Square and marched to the Town Hall where a message was read. The Limerick Leader of October 6th gave the march much exposure. The newspaper covered the following message which was read to the workforce and the many others who took part in the march.

"This march is a token of the respect with which the employees of Ferenka and the citizens of Limerick and region regard Dr Herrema. In all our consultations with him, since his arrival, he has always shown a keen awareness of the problems of the workforce and a genuine concern for their wellbeing. This march also reflects the leading position, which Ferenka has played in the developing industrial capacity of the area. The reader went onto relate that the abduction is “completely unrepresentative of the positive feeling which Limerick and indeed Ireland adopts to companies bringing factories and jobs to this country."

The Limerick Leader of Saturday, October 11th ran with the editorial headed "Tiede Herrema. Limerick's Friend' The article expressed the "abhorrence of politically motivated gangsterism”. Dr Herrema's plight was a “cause of sincere concern but no where has the anxiety been more painfully felt, and the sense of outrage more strongly expressed than on Shannon side”.

It goes on to express the deeply held views of all the interviewees that Dr Herrema was respected “as a professional at his job and was genuinely liked as a person of consideration and kindness”.

As Dr Herrema remained in captivity, the search for him widened. Some mediators had been contacted, and negotiations regarding a ransom for Dr Herrema began. One negotiator Fr. Donal O’Mahony OFM Capuchin told of his Ferenka story in this way:

The late Cardinal Alfrink of Holland had been in consultation with the parent company of Ferenka in Holland. The Cardinal wondered if Fr. O'Mahony could go as a ·go-between" because it seemed that the life of Herrema was in danger. Fr. O'Mahony continued: "The Cardinal knew me personally, as I had been an executive member of an international Catholic movement for peace, Pax Christi International and the Cardinal was its President'. To continue with Fr. O'Mahony's memories: He offered himself as a "contact" person on behalf of the company if the kidnappers wished to avail of a third party. "Unfortunately, in those early days no one was sure who the kidnappers were, and so we had no alternative but to announce it publicly on the RTE evening news and simultaneously in the news telecast in Holland, hoping the kidnappers would see or hear it on the radio". Fr. O'Mahony went on to relate that "the initial publicity subsequently became a real difficulty for me. The kidnappers did make contact with him within a couple of days through a tape.

Dr Teide Herrema told Fr. O'Mahony later during a round of golf in Castletroy, how disappointed he was that the kidnappers ordered through him, that the Ferenka Company be closed. Fr. O' Mahony believed the closure to be ' only for a specific duration·. As for the subsequent effects this episode had on the life of Fr. O'Mahony, he went onto relate: "it catapulted me more into the international arena and was also the reason for my later involvement in other involuntary incarceration cases in Southern Italy and Central America.

Dr Teide Herrema told Fr. O'Mahony later during a round of golf in Castletroy, how disappointed he was that the kidnappers ordered through him, that the Ferenka Company be closed. Fr. O' Mahony believed the closure to be ' only for a specific duration·. As for the subsequent effects this episode had on the life of Fr. O'Mahony, he went onto relate: "it catapulted me more into the international arena and was also the reason for my later involvement in other involuntary incarceration cases in Southern Italy and Central America.

As well as the negotiations which went on to secure the safe release of Dr Herrema contingency plans had to be prepared. As one source put it, "if he was found and released what would be done?" Dr Stephen Flynn was involved in these contingency plans. He gave me the following account of his Ferenka experience in this regard.

The plans "were more or less finalised and clarified when the siege started in Monasterevin". He recalled getting a call on a weekday night, "to go immediately to Monastere vin".

Dr Herrema had been located. Dr Flynn recalled it being a "very foggy misty night getting up there.

There was quite a lot of confusion around the place meeting various guards and emergency procedures which were in place. There was a great encampment of Press, and they had bonfires lit. He also recalled a private ambulance service which was run by a man called Gleeson in Dublin. There were one or two ambulances permanently there during the siege available if Dr Herrema was released if there were any injuries. There was one injury during the siege itself.

Speaking of the contingency plans, Dr Flynn continued: “We had to make contingency plans, where would he go, what would he do, we were involved with that". The Dr. recalled going to the Ambassador Hotel in Kill, where he met with the Garda Commissioner, Des O'Malley, a representative of the company, a representative of the Dutch Embassy and somebody from the army. They were all working out these plans·. "The original plan was to go to the Curragh Military Hospital".

On November 7th Dr Herrema was freed. Dr Flynn recalled: "On his release, he did not go to the Curragh Camp, but instructed his driver to take him straight to the Dutch Embassy, as he felt he didn't need medical attention. Again it was a very misty night". Dr Flynn continued "I remember driving up late at night to the Curragh Camp with special instructions to identify yourself, etc." However, as Dr Herrema was not there, Dr Flynn was directed on to the Embassy.

This was not part of the original plan, "but ultimately we got as far as the Embassy, and then I saw him that night. Dr Flynn went on to describe Dr Herrema as a man of "great inner strength". After his ordeal Dr Herrema was suffering from some minor injuries, "he had injured his hand and a broken tooth, but apart from that mercifully he was fine".

The injury to Dr Herrema's hand is explained in more detail on the Evening Echo on Tuesday, June 9th, 1998. In an article by Bernie English, entitled "The longest kidnap drama· it states the following: "The unfortunate businessman lost his little finger, which was cut off by kidnappers Eddie Gallagher and Marion Coyle. The pair sent the digit in the post as proof of their intentions if their demands were not met".

To conclude this episode, Dr. Herrema was given honorary Irish citizenship by the State. Limerick County Council presented the Dutch Industrialist with an "illuminated address". The City Council debated on giving Dr Herrema the freedom of the City, but this did not come to fruition. However, the Mayor did host a reception for Dr and Mrs Herrema on December 7th.

On a lighter note, the Sports and Social Club was described as "one of the few bright spots of Ferenka". For a fee of just two pounds. Employees were entitled to membership to this club. The Sports Club played "all sorts of games, soccer, hurling and they had a golf society". According to one former employee, ''they played a lot of inter-firm matches like hurling and soccer". He went on to relate that "they had some nice hurlers because they'd a great pick from all over the county and outside of the county". However, there was not any recollection of them winning any major games in this field. The golf society was "very successful and very active”.

One former member recalled the Society getting six or seven bookings during a season in various golf clubs throughout the area, and "that's where they would play their games". The Ferenka involvement in Tops of the Town was expressed as a "plus within a plus", being as it was part of the Sports and Social Club's activities. Tops of the Town was very popular in the Ireland of the 1970s. It was an inter-firm talent show, the various heats being played out in front of large audiences, in different theatres throughout the country, culminating in the final being televised by RTE from the Gaiety Theatre in Dublin. Gay Byrne hosted it for many years.

Ferenka never won the Tops of the Town Final outright, but in 1977 they did get to the final with the show Steel a Cord. In the Limerick Leader of May 28th, 1977, Tony Liddane Personnel Officer at Ferenka described their success in qualifying for the finals of the John Player sponsored Tops of the Town competition at Mosney. He said: "Naturally everybody in the giant Ferenka plant in Annacotty was thrilled when the news leaked through last Monday that their Tops of the Town group had qualified for the Gaiety Theatre in Dublin", said Mr Liddane. "It is no secret that we have our share of problems since the factory got underway, and this is perhaps the best thing that has ever happened to us. We are now being projected in a new light and are keeping our fingers crossed that we will come out tops when we meet the holders, ACEC (Waterford) next month". However, it was not to be. Their Waterford opponents beat the Ferenka show.

Up to this point, the Tops of the Town was the preserve of Banking and Insurance firms. A former employee told me "that Ferenka pioneered foreign companies partaking in such an event'. A comedy committee wrote the scripts for the show, and a musical committee decided on the music. As to financing the shows, one source stated, "the company helped greatly, and we did make collections amongst ourselves as well”. He went onto relate "of course the further you get with Tops; you got a few quid from John Player, who was the sponsor at the time". As to the number of people involved, anything up to seventy people would be associated with the show. There was also "great support from the husbands and wives or the partners involved". Pat McGann produced and choreographed the shows along with his wife. It was also noted in the Limerick Leader of June 18th 1977 that the Tops of the Town contest helped to raise money for charity. The Limerick CBS building fun and the Saint Vincent de Paul Society have "been the main beneficiaries in the Limerick area”.

Another interesting aside to Ferenka's involvement with Tops of the Town was the fact that they got to the semi-final which was held in the Cork Opera House the following year "with a show called Circassia", and "were beaten rather unluckily". As one former employee readily admitted "it shows you the spirit of the lads and lassies involved. Ferenka had closed at the time, and we kept the show going despite that. It just shows you what the spirit was like!" It was brought to my attention too, that Ferenka's owners in Holland contributed very generously to the Circassia show, even though they were gone out of Ireland at this stage.

The reasons for the closure of the Ferenka Factory are as profuse and as varied as the number of people interviewed. Many of the reasons have been alluded to already. There was inter-union rivalry, rigid management and bad pay and conditions for the workforce in general. Another reason for the closure of the Ferenka plant was the non-availability of a market for the product. Many former employees, at management level within the factory, have attested to this fact. The inter-union rivalry was ·secondary. One former employee described it thus: "demand was dropping for the product, (steel cord for tyres).. He believed the steel cord was being replaced by fibreglass.

Another former employee who held a managerial position put it more succinctly. He said that there was very limited knowledge of steel cord manufacture, and "we weren't very good at it".

The product (steel cord) was mainly manufactured for Goodyear in the USA. Goodyear in tum was competing with Michelin, who were able to remould their tyres ten to twelve times. Goodyear was "into steel cord and could not do that procedure like Michelin, and hence changed the rubber to resolve this.

The adhesion between the new rubber and Ferenka's steel cord was not satisfactory. That was the core problem". Another source explained the reason for the failure of the Ferenka plant as a "lack of correct market to match the production facility here."Add to this the fact that the company lost millions during the Herrema kidnapping, and "they couldn't afford to lose that either". That also affected their relationships with their customer's companies like Goodyear and Pirelli.

The last major strike, which took place at Ferenka, which was blamed for facilitating its ultimate closure, began with an unofficial stoppage, which lasted only a few days. With subsequent suspensions, a further strike took place, which "precipitated the final stoppage”. During this time most of the workers defected to the MP & GWU. To quote Joe Wallace, "this transfer was resisted by the IT&GWU, thereby leading to an inter-union conflict.

After a prolonged and bitter dispute, the workers returned to work, but production was not resumed. On November 28th, 1977 the decision to close was announced on the evening news. The company cited• substantial losses suffered by Ferenka, aggravated by the recent strike. And prior repeated work stoppages, plus the loss of confidence in the possibility of achieving a workable solution, had forced this decision on them"(Taken from the Joe Wallace report Industrial Relations in Limerick City and Environs).

Another reason cited for the failure of Ferenka was that AKZO were rationalising "all around the place and that Ireland was becoming a too high labour cost country for a company like that".

When Ferenka did finally close its doors on November 1977, there was a sit-in protest, against the closure. The sit-in did not prove to be successful, and the announcement on 28th November was the "final nail in the coffin for Ferenka". Some of the former employees were "taken on again by the liquidators. When they moved in to quote one former employee 'it was soul-destroying'".

The Ferenka story has ofttimes been told. This article intended to bring you the people behind the headlines.